Fighting for property owner’s view rights!

On September 18, 2024, the California Supreme Court granted Turner Law’s petition for review in Cohen vs. Superior Court (Schwartz): “The issue to be briefed and argued is limited to the following: “Does Government Code section 36900, subdivision (a) confer upon private citizens a right to redress violations of municipal ordinances?” That statute provides in part: “The violation of a city ordinance may be prosecuted by city authorities in the name of the people of the State of California, or redressed by civil action.” (emphasis added)

In other words, at issue are property owners’ fundamental right to file a civil action to seek enforcement of a local building or zoning code ordinance that is intended to relate to view protection.

Please CLICK HERE to contact us if you want further information.

Uninvestigated Violations: The fundamental concern here is the City of Los Angeles’s limited and seemingly selective enforcement of fence and hedge height violations, which raises significant questions about equity and fairness in urban governance. Many residents have expressed frustrations, feeling that certain neighborhoods are scrutinized more closely than others, leading to a perception of bias in the enforcement process. The City of Los Angeles’s position is that citizens do not have the right to seek redress for code violations, leaving many individuals feeling powerless against the arbitrary application of these rules. Furthermore, this situation can create negative ramifications for community harmony, as residents may feel they are at the mercy of an inconsistent regulatory framework. For those interested in deeper legal implications, click here to review the City’s “Amicus” brief that it filed in the Court of Appeal to better understand the official stance and the arguments being made regarding these pressing issues.

BACKGROUND

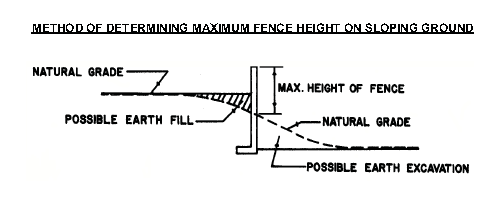

The Turner Law is often asked by property owners for legal help when a neighbor is violating a building or zoning code provision related to view protection, such as a local fence or hedge height ordinance. These violations can be particularly frustrating, as they not only obstruct scenic views but can also impact property values and the overall enjoyment of one’s home. Many cities and towns in California recognize the importance of preserving views and limit the height of fences and hedges in residential areas to six feet. This regulation aims to maintain a sense of openness and aesthetic appeal in neighborhoods, ensuring that homeowners can enjoy their beautiful surroundings without excessive obstruction. In addition to legal advice, the View Rights Center assists residents in navigating the complexities of local ordinances, empowering them to enforce their rights effectively while fostering goodwill and cooperation with neighbors.

In 2002, the Second District Court of Appeal in Riley v. Hilton Hotels Corp., 100 Cal. App. 4th held that Government Code section 36900 allows a private party to sue for redress for violation of a Municipal Code.

Using 36900 to enforce hedge and fence height law (Riley)

For instance, based on Riley a homeowner in Morro Bay brought a civil action because the City refused to enforce its hedge height law, because the City deemed the Myoporum to be trees, not hedges, and that “‘the code [section limiting the height of hedges] doesn’t limit the height of trees.'” Kraus v. Grilli (Cal. Ct. App., 2015) The neighbor had replaced eucalyptus trees with a row of five or six “fast-growing” Myoporum laetum shrubs (Myoporum) that were planted along the boundary. By the time of trial, the Myoporum had grown to a height of approximately 23 feet

and a length of approximately 50 feet. The plants blocked sunlight and respondent’s

ocean views.

During the trial, the judge visited the parties’ residences and viewed the Myoporum. The judge determined based the nature, size, location, and purpose, the Myoporum constitutes a hedge and fence within the meaning of the Morro Bay Municipal Code.” The court determined that the hedge was a private nuisance and was in violation of the municipal code’s height limit of six feet, six inches. The judgment ordered a “permanent mandatory injunction requiring the neighbor or any other successive owner to “either remove the hedge in its entirety or remove “at least 5 feet of the mature canopy per year . . . to a maximum height not to exceed six feet, six inches.”

On appeal, the neighbor argued that the property owner did not have standing to enforce compliance with the height ordinance. The neighbor argued: “This Court should reverse the trial court to discourage officious private citizens from using

their neighbors to enforce local ordinances. If [as here] the ordinance is silent on standing, enforcement is best left to the city that created the ordinance and can best show meaningful restraint in resolving disputes as the City of Morro Bay did here.” “If an ordinance should be privately enforced, that right should be conferred by the city that authorizes the ordinance, not seized by private citizens with the resources to hire lawyers.”

The Court of Appeal rejected that argument based on Riley, stating: “Respondent had standing to enforce the ordinance. Government Code section 36900, subdivision (a), provides: “The violation of a city ordinance may be prosecuted by city authorities in the name of the people of the State of California, or redressed by civil action.” This section “expressly permits violations of city ordinances to be ‘redressed by civil action.’ … [Appellant] refer[s] us to no state law that allows a city to abrogate the right of redress created in the Government Code. We decline to read into the Municipal Code an intent to create an impermissible conflict with state law by abrogating the right to a civil action created by the Government Code.” (Riley v. Hilton Hotels Corp. (2002) 100 Cal.App.4th 599, 607.) Thus, the Court of Appeal affirmed the decision in an unpublished decision.

Based on Riley and Krauss, many civil actions have been filed to enforce local hedge and fence height regulations, as well as other important land use laws. These legal disputes often arise when property owners believe that their neighbors are not adhering to established height restrictions or are otherwise misusing their land in ways that infringe upon the enjoyment and value of adjacent properties. The local governing bodies often do not have the resources to investigate and enforce these laws, leading to a backlog of complaints that remain unaddressed for extended periods. Moreover, local officials often do not want to get involved in neighbor disputes. Sometimes it seems that favoritism is being used. This often results in residents feeling frustrated and powerless while their neighbor violates the law. If local officials do not have the resources or wherewithal to enforce their own laws, property owners should be able to seek redress through civil action.

Schwartz vs. Cohen

Homeowners in Brentwood had asked their neighbor to trim his hedges that were blocking their view. When he refused, the homeowners filed a code enforcement complaint with the City. Because the City had not even started its investigation, the homeowners filed a civil action. Because the trial court overruled (denied) the defendants’ demurrer, the defendant retained one of the most well known appellate specialists to file a writ, which Second Appellate District granted on June 5, 2024, Cohen et al. v. Superior Court Los Angeles County et al., (Case: B330202). The Court of Appeal certified its opinion for publication. The court concluded “the doctrine of stare decisis does not prevent us from reexamining and disagreeing with Riley. Thus, we overrule Riley and disavow its recognition of a private right of action by members of the general public under section 36900, subdivision (a). We therefore will issue a peremptory writ of mandate as requested by the Cohens.” To be clear, we hold only that section 36900 does not authorize private parties to bring civil suits to enforce local ordinances. We do not disturb caselaw recognizing that, in some instances, a defendant’s violation of a local ordinance may be relevant to, or provide an element of, some other cause of action by a private party, such as nuisance or public nuisance.”

Supreme Court Review

Attorneys affiliated with the View Rights Center filed a petition for Supreme Court Review. Other attorneys filed amicus briefs.

On September 18, 2024, the California Supreme Court granted the petition as follows:

| The petition for review is granted. Pending review, the opinion of the Court of Appeal, which is currently published at 102 Cal.App.5th 706, may be cited, not only for its persuasive value, but also for the limited purpose of establishing the existence of a conflict in authority that would in turn allow trial courts to exercise discretion under Auto Equity Sales, Inc. v. Superior Court (1962) 57 Cal.2d 450, 456, to choose between sides of any such conflict. (See Standing Order Exercising Authority Under California Rules of Court, Rule 8.1115(e)(3), Upon Grant of Review or Transfer of a Matter with an Underlying Published Court of Appeal Opinion, Administrative Order 2021-04-21; Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.1115(e)(3) and corresponding Comment, par. 2.) The issue to be briefed and argued is limited to the following: Does Government Code section 36900, subdivision (a) confer upon private citizens a right to redress violations of municipal ordinances? Votes: Guerrero, C. J., Corrigan, Liu, Kruger, Groban, Jenkins and Evans, JJ. |

Under Supreme Court Rules, the opening brief is currently due by October 18, 2024. This timeline is crucial, as it sets the stage for the case to unfold in the legal system. An important legal right to seek “redress” by civil action is at stake, which plays a pivotal role in ensuring that individuals and entities have the opportunity to address grievances and seek justice. Without that right, property owners’ rights are severely limited, restricting their ability to challenge injustices or unlawful actions against their property. Therefore, taking timely action is essential.

Please CLICK HERE to contact us if you want further information, as we are ready to assist you in navigating these complex legal challenges and ensuring that your voice is heard.

(by Keith Turner, Esq. and Emma Samyan, Loyola Law School, J.D. Candidate | Class of 2018)

(by Keith Turner, Esq. and Emma Samyan, Loyola Law School, J.D. Candidate | Class of 2018)